India

Once across the border into India we immediately felt the change. We had entered Bihar, one of the country’s poorest states, although that cannot excuse the experience of trying to drive across its territory. The roads in particular were almost criminally dangerous with no apparent rule other than the pre-eminence of road-mass. Even the use of the horn was indiscriminate, used to jostle rather than communicate, while we often only avoided head on collisions by driving off the road or just stopping to give the overtaking vehicle coming toward us sufficient time to pull in. Once off the road there are very few places to stay and the motels we did find were seedy affairs even by our lowest standards. At one Ruth had to discourage the manager who used a pretext to get me out of the room so he could be alone with her for a short while – something he probably regretted. Finally, the Landyvan, always a thing of interest for locals, began here to feel more like an ostentatious liability, an unfamiliar experience fortus. All this did not amount to a rosy introduction in India, a place that we had hoped to spend many months touring before returning home.

After a few more incredulous incidents we reached Calcutta (or Kolkata in its new more phonetic Indian spelling) and dropped the car like a hot potato into the car park at the airport. We had booked flights for a Christmas and New Year holiday on the Andaman Islands and negotiated with the car park manager a long term arrangement for a minimum of 30 days. We were not keen to return and felt like we deserved our vacation.

India’s surprises did not get left with the car however. When we appeared for check in at the airport the next morning we were told, along with the other foreigners on our flight that our VISAs did not cover the Andaman Islands and we were not to be allowed on the flight. After disbelieving tears and arguments the airport manager was eventually browbeaten into calling his opposite number in Port Blair and this decision was suddenly and inexplicably reversed. Although this does not sound like the makings of a love affair with India, things did get better…

Once off the plane in Port Blair we smoothly made our way through the permit process as expected from the outset. We caught the early ferry to Havelock and were on the beach before we had started thinking of lunch. Although it took Ruth a couple of days to repair frayed nerves this was starting to feel more like it.

The Andamans are a small group of islands more local to South East Asia than the India to which they belong. They, along with the neighboring Nicobar Islands, form the peaks of an underwater mountain range. Only a few of the Islands are inhabited and some of these by tribes protected from external contact. Their most recent claim to fame is as the epicenter of the 2004 earthquake that triggered the tsunami that wiped out settlements on many of the Islands, although apparently the indigenous people had long fled to high ground after reading signs of the impending doom in the natural world around them. The most lasting sign of damage is the change in sea level, which is as much as 4 meters in some areas of the islands.

Havelock is one of the largest of the Islands and the most geared up for tourism, although that is not saying much. Along with indigenous locals most of the people are fishermen from West Bengal or Indians attracted by the easy lifestyle. We are generally good with easy lifestyles and found it straightforward to fit in, spending our days either scuba-diving or scootering around the island searching for snorkeling spots. We were far from the only ones attracted to this lifestyle and made a great number of international friends, spending Christmas and New Year in their company, all similarly dislocated from home and family.

Christmas was a mix of the traditional Western and Indian: Secret Santa and Tandoori chicken. Ruth in particular excelled at the parlor games, coming out tops with her ability to pick up a credit card from the ground with only her mouth and feet allowed anywhere near the floor. For New Year we joined our imaginative friend Claire to introduce a new tradition: Inspired by the Burning Man festival in California we built our own Burning Andaman into which everyone was encouraged to stick slips of paper outlining their regrets and highlights of the year past and their hopes and resolutions for the year to come. For a new tradition it seemed to catch on.

After our month of constructively doing nothing we were sorry to leave our friends and head back to the mainland. While away we had made one small modification to our travel plans: Where we had intended to spend some months driving around India before returning to the UK by an alternative route our New Year resolution was to continue to Australia. Our earlier experiences had informed us that India was a country better travelled by train, the distances are simply too great and the hazards too real for driving to be considered an enjoyment. We also found it hard to be inspired by any of the route options back to the UK, as they either felt like old routes already trodden or new ones but in the wrong season. By contrast, we were genuinely excited by being able to spend some time travelling through South East Asia and our Landyvan would come into its own in the vast empty spaces of the Australian Outback.

We still faced the perennial over-lander’s problem: Myanmar. Burma still refuses to allow overland travel across its borders. This leaves only two options: backtracking through Tibet and Yunnan provinces in China before dropping into Laos or alternatively shipping, either to Singapore or directly to Freemantle. Although not quite as romantic, we could not argue with the excessive cost of the overland route through China and chose instead to ship from Chittagong in Bangladesh. We also decided that we would save the unpacking and repacking in Singapore and ship directly to Australia, while we travelled overland through Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore and Indonesia without our faithful Landyvan friend. We also thought this would be a good time to inform our ever-accommodating employers that we would not be back at our desks after 9 months, but would instead be lost for more like 13. This was all in the future, however it is sometimes nice to have a plan.

Rather than fly back into Kolkatta we chose instead to return to the mainland via Chennai. This gave us the opportunity to visit a couple of places in the South of India. We started in Pondicherry, travelling with our Andamans friend Claire. Pondy, like many Indian cities, has two sides: a chaotic Indian side of colour and occasional strangeness, such as the elephant that gives blessings in return for money; the other side is its French colonial past with a heritage of elegantly faded architecture and some great places to eat out.

Arguably the third side to Pondicherry is the legacy of Sri Aurobindu, an Indian who set up an Ashram in the city, and a French disciple of his: The Mother. The ashram’s activities crop up all over the city: originally formed as a retreat that did not prescribe any fixed form of meditation, yoga or devotional method, there now appears from the outside to be a significant amount of hero worship for Sri Aurobindu, The Mother and their writings. The Mother’s most obvious legacy is Auroville, a new town that she started on the outskirts of Pondicherry as an experiment in more harmonious international living. There is a lot more to the idea than this, including some fairly demanding practices and aims prescribed by The Mother that the residents are left to struggle with now that she has left her earthly body behind.

While in Pondy we stayed in the Ashram guest house, a 60s building plucked from a European sea front, which we loved for its honest artistic touches, reasonable price and central location. The room booking policy seemed a little arbitrary and we felt like we had to prove our sincerity to be allowed to stay. The majority of our time we spent enjoying the architectural touches of the old city and wandering the sea front, strangely reminiscent of English sea side if it were not for the hawkers and fortune tellers. The latter made their predictions based on tarot cards picked from a pile with great conviction by a parrot. Ruth can look forward to a long life (good), to a non-arranged marriage (a very positive outcome for an Indian) and to running her own factory (possibly a new Indian aspiration, but also not wide of the mark for Ruth).

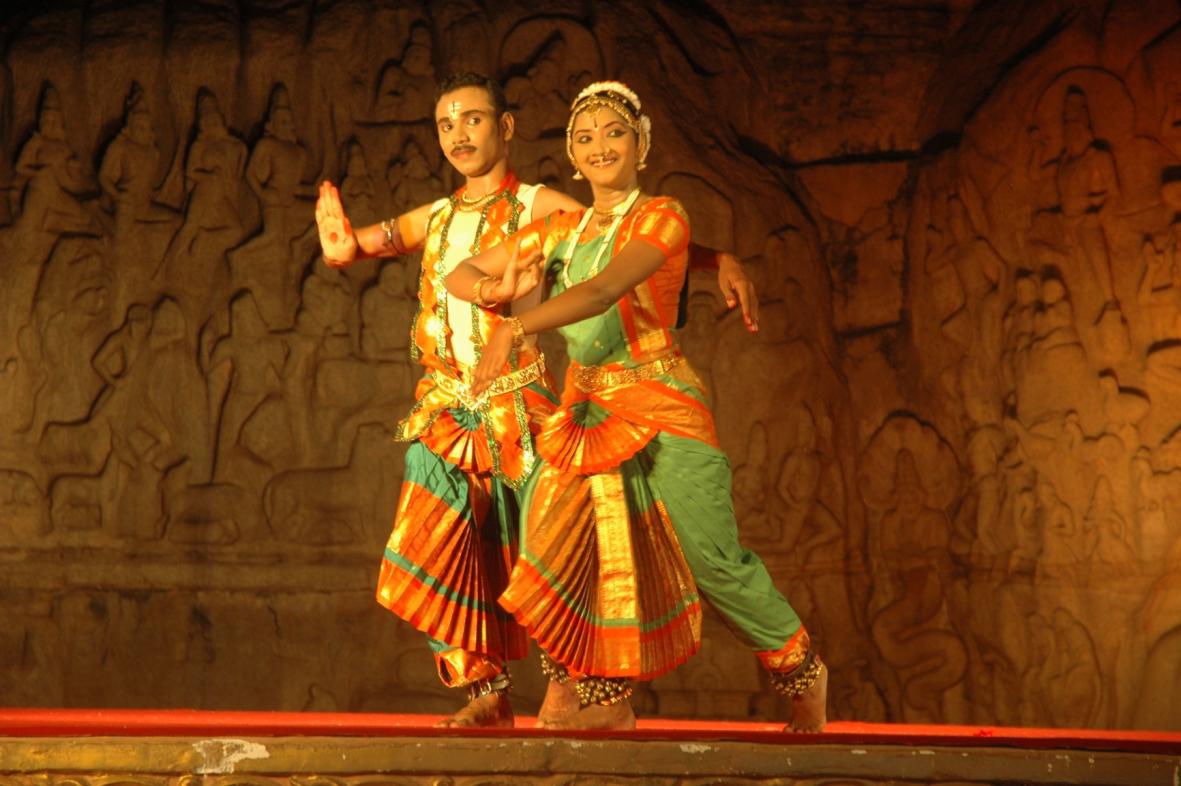

We said our sad goodbyes to Claire and returned to Chennai where we would catch an onwards flight to Kolkatta, but not before visiting Mamallapuram. This is a Tamil Nadu sea side town made famous for its rock carvings and stone temples, the most famous being the Shore Temple and Five Rathas, both erected by the Pallavas kingdom sometime before 850AD. We spent our stay attending the awesome traditional dance festival, eating some outstanding sea food and wandering around the monumental stone carvings. The most impressive of which were hewn directly from the rock face – no assembly required.

We returned to Kolkatta significantly more at ease with India than when we had left. We could still catch glimpses of what had irritated us before, and we were still not relishing getting behind the wheel again, however we were now beginning to see India’s strengths in the friendship, intelligence and humanity of its people. As a result we enjoyed our stay in Kolkatta, unfortunately extended by Ruth’s tendency to catch diseases such as Typhoid and by the Bangladeshi embassy’s last minute holidays just as we were expecting a VISA from them.

With Ruth in bed I did not stray too far from our guest house. However, my constant comings and goings soon made our local neighborhood familiar territory. On our corner just off Park street were many of the best restaurants in Kolkatta, we could have breakfast in Flury’s, a sort of colonial art-deco tearoom, a Thali lunch at Gupa Bros. and dinner in Mocambo, all for under £5 a head, a fortune in India admittedly but I was eating for two. Our corner was also host to a rickshaw stand, all familiar smiles and bells jangling when I passed, as well as a number of beggars, their crippled limbs, handfuls of roses or small children on show. These latter elicited differing levels of sympathy in me depending on their tactics and my prejudice of need - it soon became a habit to collect small change for favorites. In this way a small corner of a very cramped, polluted and noisy city displaying gross extremes of poverty and wealth began to feel surprisingly homely.

After Kolkatta we headed West again, intending to find our way back to Nepal. This time we were prepared for the roads and planned accordingly: We researched easily achievable overnight stays with tourist interest, we avoided driving through the back roads of Bihar and finally we locked our sanity firmly away where it could not be tempted into madness by obviously loony fellow road users. In this way we made it alive to Bodh Gaya, site of Buddha’s enlightenment and then to Varanasi. In Bodh Gaya, we had just missed an annual visit by the Dalai Lhama, and as a result the town was thronged with exiled Tibetan monks. We spent part of the evening joining them in a kora of the temple, marveling at the gaudy display of light and colour so outside our experience of Buddhist culture in Tibet. The following morning we were on our way again, but not before taking a tour of an orphanage with some local boys we met the evening before. The orphanage takes in boys from all over Bihar as well as schooling local children in a building clearly maintained with the minimum of funds – part of a worthy focus on humanity and education that seems common throughout India.

In Varanasi we met up with Marie, another friend we had made in the Andamans. We had been dreading our arrival into Varanasi, a city known more for its devotional chaos than for its concessions to cars, however Marie did our research for us – finding a parking spot, negotiating the price beforehand and giving us detailed instructions “ask locals for Assi Ghat then phone me!” She even found us a room in her home, a house managed as part of a foundation to provide accommodation for foreign students studying all things Indian. Marie herself is studying Indian Philosophy at Benares Hindu University, others were studying Sanskrit, Yoga, Indian music etc. We could hardly have asked for better informed guides, even their adopted puppy was a welcome relief from the fate of the other street dogs we had seen in Nepal and India.

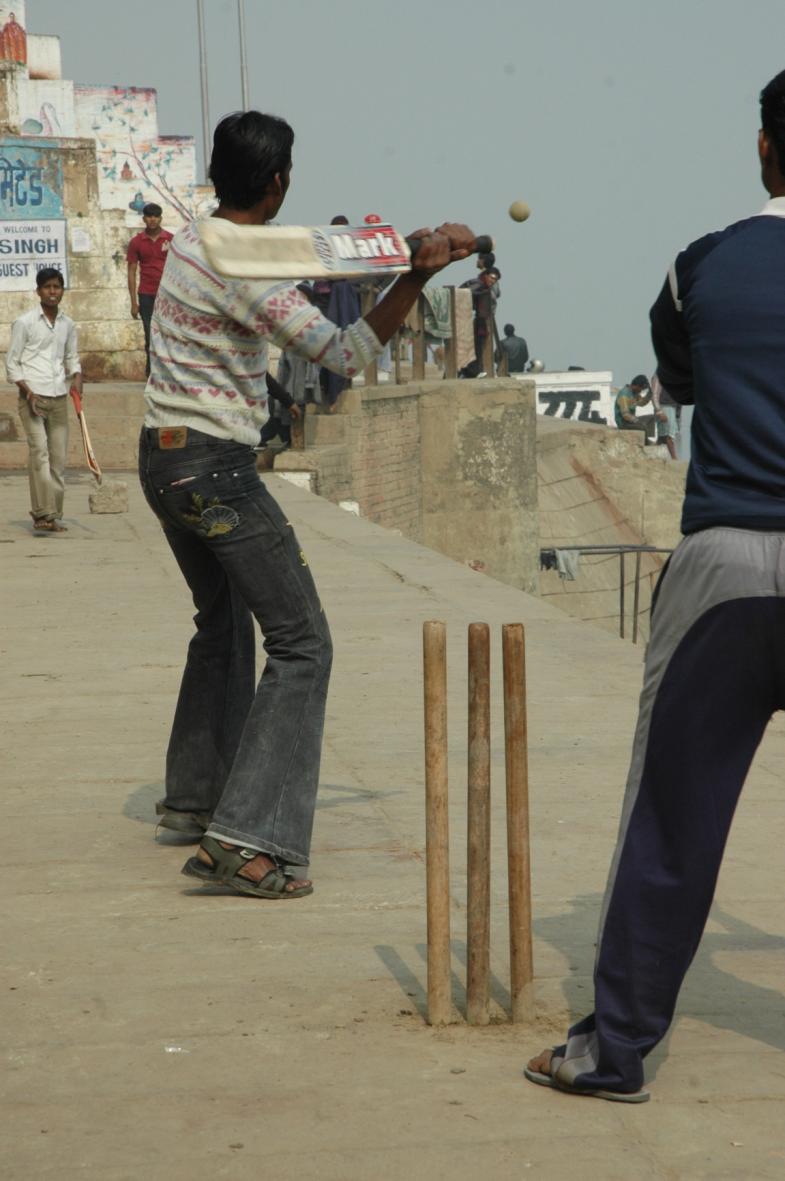

We spent our time in Varanasi soaking up the atmosphere of this most holy Hindu pilgrimage, standing as it does where the Holy Ganges, or Ganga, momentarily runs North on its otherwise Southern journey. I soaked up a little too much, catching a chest infection that led to pleurisy and a lot of pills. Apart from this it was an exciting city to wander in, most particularly along the Ghats – the steps arranged in chaotic columns all along the banks of the Ganges. Here is all of Varanasi and occasionally India: including kids flying home made kites or selling floating devotional candles; hawkers selling food, beads, souvenirs and boat rides; hundreds of city cows joining the more usual homeless dogs; games of cricket where one boundary is the flood walls and buildings and the other is the river itself. The Ghats are also famous for their religious ceremonies, from the everyday washing and Puja to the open air Hindu cremations that are held in dedicated locations, the shaven-headed men folk standing around the pyre while the women stand some way back. There is apparently an effort underway to clean the water of the Ganges including an electric crematorium as well as several water purification towers, apparently much needed.

The drive from Varanasi to the Nepalese border took just over a day and was relatively uneventful. However the sensation we had on crossing the border and heading into the hills beyond the Terai in Nepal came as quite a surprise: It was pure relief – we had simply not realized how tightly wound we had become travelling our short distance through India. The press of humanity is so great and the noise, colour and complexity so overpowering that it had simply become part of our every day landscape of experience. It was only when we were reunited with the peace, slow pace and easy “Namaste” of the Nepalese that we became aware by contrast. This is not a detraction of India, which we had grown to love for the involvement it demands, however a little part of our soul was happy to only have that experience in small doses. In fact it was in the details that we found greatest contentment: taken as a whole India was a landscape of confusion and contradiction, however at the level of small experiences, of portrait and still life, it began to make a little more sense.

Last Updated (Monday, 12 April 2010 11:01)